This is a popular corporate syndrome that was often mentioned as part of Microsoft’s organizational culture back in the late 90s/early 2000s. Being that it was org culture, it kept popping up in different ways. For example, in the early days of the Internet, Microsoft chose to keep the ‘Net at arm’s length; they would create competitive products (sometimes using the same underlying protocols or different dialects). Eventually, they came to their senses and decided to stop fighting it and love the ‘Net.

Similarly, they would purchase competing products and often bury them. Product review would skew in favor of their own, internal efforts, perhaps with approaches from the former competitor. Or perhaps not.

As an IT leader, the same thing happens in our own development. The skills that made you the best, fastest diagnostician on the Help Desk, or the best IT Architect, often fall short when you’re faced with dealing with your staff or even going through a decision process on a new Managed Detection & Response service. You’re not alone — it behooves you to remember that others have probably walked in your Allan Edmonds.

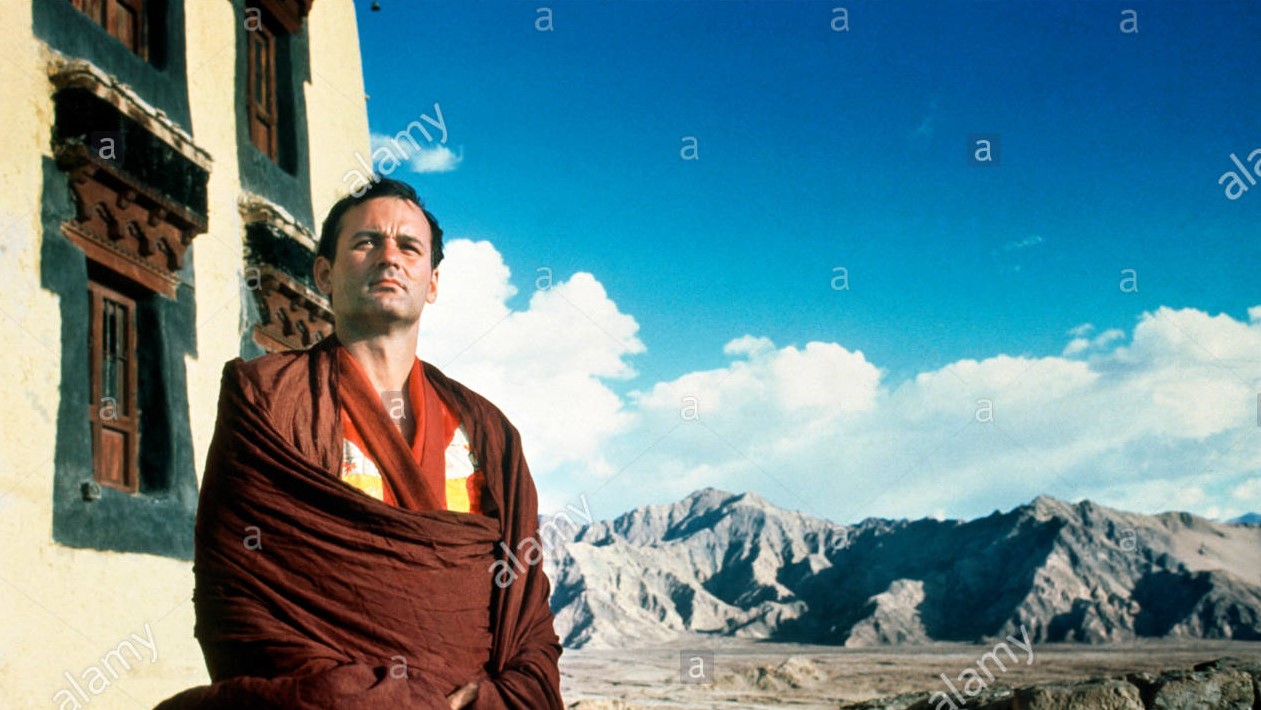

Which is why it’s important to remember that you’re part of a larger whole: I’ve loved being a part of the Tulsa CIO Forum here in Tulsa, and the Washington State Community & Technical Colleges Information Technology Commission. In both cases it gave me a chance to “confer, converse, and otherwise hobnob with my brother Wizards” — (name the movie) several times a year, and being able to reach out to solve those thorny issues together.

But one area of leadership development that IT people are usually left to their own devices is the soft skills — the things that give you the edge when you move up from being the seniormost tech to helping move the organization, as a part of an Executive Leadership Team.

Many of my colleagues who grew up in larger organizations with large IT shops have these soft skills built-in to their development, which is excellent. But those of us who came up through start-ups or smaller shops, where you’re creating the IT department as you go…we gotta get it elsewhere.

I’ve already written _ad_nauseam_ about being exposed to these as a refresher in 2018’s STF LRA classes. I’d already had these skills and used them earlier in larger organizations, but one gets rusty when one is rebuilding a small-shop IT infrastructure from scratch over the course of a few years. I thank my employer for sending me: I enjoy reading case histories about business decisions (like watching car crashes in slow motion, if you already know the outcome!), and among the books we studied was Jim Collins’ “Good to Great.” If you’ve read it, you know the approach is heavy on examining benchmarks and comparisons of companies that have weathered the storms and withstood the tests of time.

The stylistic approach of Good to Great was followed, though not so deeply, in “The CIO Edge” by Graham Waller, George Hallenbeck, and Karen Rubenstrunk (Harvard Business Review Press, 2010). The three authors are principals with Gartner and Korn/Ferry International, and much like Good to Great they draw on their companies’ research on IT trends and extensive empirical data on leadership capabilities as a foundation.

Like so many business books, the subtitle gives you a hint of what you’ll be learning: “Seven leadership skills you need to drive results.” The book is broken down into these 7 chapters, with two at the end to wrap it all up into a cohesive package — reminding you that the big professional payoff is to deliver business results.

Being that the message is about ways an IT leader needs to cultivate their softer side/people skills, the book doesn’t have the heavy statistical notes of Good to Great. Instead, it’s heavy with anecdotes from successful CIOs that describe where they’ve utilized these approaches: to remember that while they are Coaches and Mentors to their IT teams, their new primary allegiance is to the COMPANY, via their fellow Executives. An enlightened CEO would remember that, similarly, his/her role is to be a Coach and Mentor to their Executive Team members. The reality is: you’re going to have to develop deep sideways relationships with your new team, your fellow leaders. There are also examples of working well with the informal leaders within an organization — perhaps these folks hold Informational Power or Expert Power, but you need to know how to work with them for the good of the organization.

One of the real-life takeaways since reading this: in Director or VP interviews, you’ll see job descriptions that give lip service to these important collaborative skills. But in the interview itself, a great amount of time will be taken not with you citing examples of your use of those soft skills, but with the more traditional litany of reciting the protocols, network approaches, security tools used, etc. etc.

This is perhaps not surprising in organizations who perhaps have yet to embrace that long term success is more and more determined by technology. You want a CIO who understands where you are today, but has an eye on where the organization will be in the future. You want a CIO who knows the entirety of your business so they can direct meaningful and efficient change now but also is a voracious acquisitor of knowledge of your competitors. And yes: you want a CIO who can find and motivate good people to man the security barricades — a necessary, but defensive posture to ensure the company’s intellectual property stays put and the trains run on time.

Between this book coming out in 2010 and the message of the STF LRA in 2018 being identical, I hold out hope that as individual IT leaders develop and use these skills, there will be organizations ready and willing to welcome those practitioners with open arms. For the good of their organizations today and into the future.

[…] of how to guide tech into being the backbone of the organization. If anyone read my earlier post about The CIO Edge, many of these new CIO types in large multinationals are even (gasp!) not trained in IT. This is […]